by Maude Leroux | Feb 3, 2017 | Executive Functioning Skills

How to understand what it means to become organized

This writing is the first in a series of writings that is going to focus on executive behavior. This is the kind of behavior we would all like to see in our children; and ourselves, to have a goal, to plan towards it, to complete it in a timely manner without undue frustration or emotional upheaval. The ability to plan activity in a step sequence requires both motor and cognitive functions. While the mind sweeps forward to set a step-by-step action in place, the body keeps up with the know-how of what a step sequence would feel like.

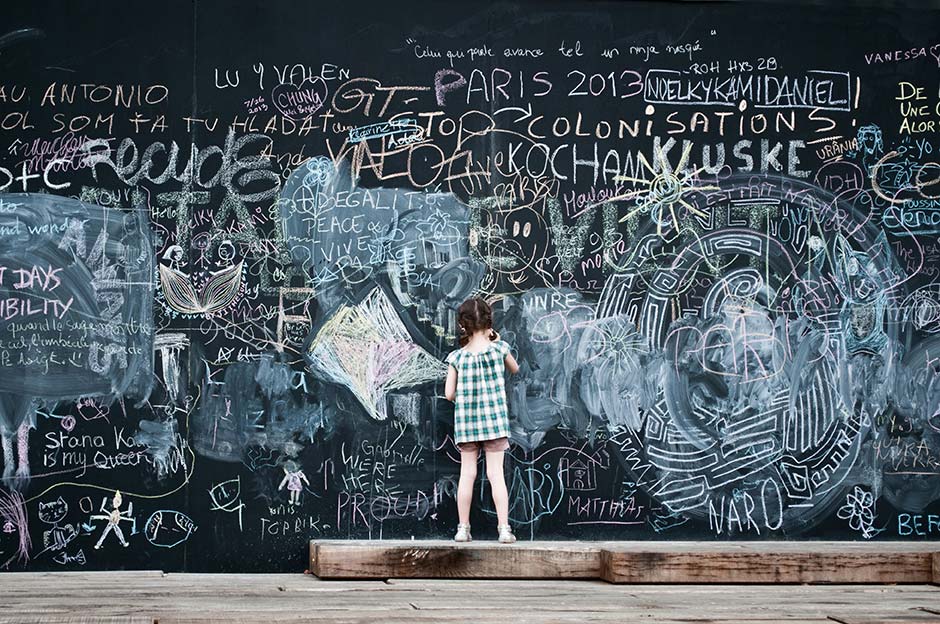

We assume she sees what we see, but for her the next step in planning is a big black hole where all the ideas are floating away, not gaining solid ground to enter into the functional process.

Let’s start with considering the ability to initiate a task. We frequently observe Sally being slow to “get going” on projects and we have to either repeat an instruction or encourage and sometimes think that she may have an attention difficulty causing her to be distracted from starting a task. But Task Initiation requires the ability to begin a task without undue procrastination, in a timely fashion, which implies that she would have an innate sense of timing in place to respond adequately. Each new task will bring the challenge of the “new and novel”, which would be difficult for her as she struggles with motor planning deficits and would have to reorganize all her systems to accommodate this new learning. As she struggles with developmental delay, she has also learned to anticipate when tasks will be too hard, just by looking at the proposed activity and will want to avoid based on memory alone.

Embed from Getty Images

The act of planning itself involves the ability to manage current or future tasks by setting goals and developing appropriate steps ahead of time. Again, being able to understand a step sequence and time lapsing are crucial skills for delivering this skill. It provides Sally with the ability to create a road-map to reach a goal or to complete a task. We assume she sees what we see, but for her the next step in planning is a big black hole where all the ideas are floating away, not gaining solid ground to enter into the functional process. Planning also involves being able to make decisions about what is important to focus on and what is not important. This requires of the brain to really need inter-hemispheric organization, because she cannot become so immersed in the detail that she forgets the “whole” of the idea she was planning towards.

The process of organizing the materials needed for a task can influence the planning potential. This requires the ability to establish and maintain a system for arranging or keeping track of important items. Systems are tough for Sally. Once she is in the moment putting a structure together, she can perhaps follow her own strategy, but a week later the same system appears to be non-existent as it never related to the level of integration required to make it permanent. Structure is important for her, but she frequently requires consistent supervision in order to maintain the structure. Once routine is established and have been repeated several times, she can learn to rely and cope with the structure in place, but the skill is not generalized over into new and novel other areas she encounters in every day life, unless someone imposes another structure to organize by. When Sally is left to her own devices, she is not able to keep track of information or materials.

Next time we will cover the concept of time and having goal persistent behavior. Stay with me as I uncover more ground as to what executive behavior really asks of anyone and in the final writings of this topic, we will cover what can be done about it. Sufficient to say at this time that you can accommodate for Sally’s difficulties, but you can also remediate, so she does not have to look back again. Executive difficulties causes great performance anxiety in children and school becomes a mass of information that cannot be structured or contained even while students like Sally have sufficient intelligence. It is not about being smarter, but having the necessary building blocks that would support Sally in automaticity and self-sufficiency.

Stay Tuned!

Maude

by Maude Leroux | Jan 9, 2017 | Parenting

The ship was full and many things were happening. Lives were connecting and the journey was on its way. The captain was steering the ship when he noticed the tip of the iceberg in his path. He did attempt to mobilize the ship around this mound of ice and felt comforted by his efforts. He did not foresee what was lying underneath the surface of the waters he was navigating. Underneath the surface was a huge amount of ice that eventually caused the destruction of the Titanic.

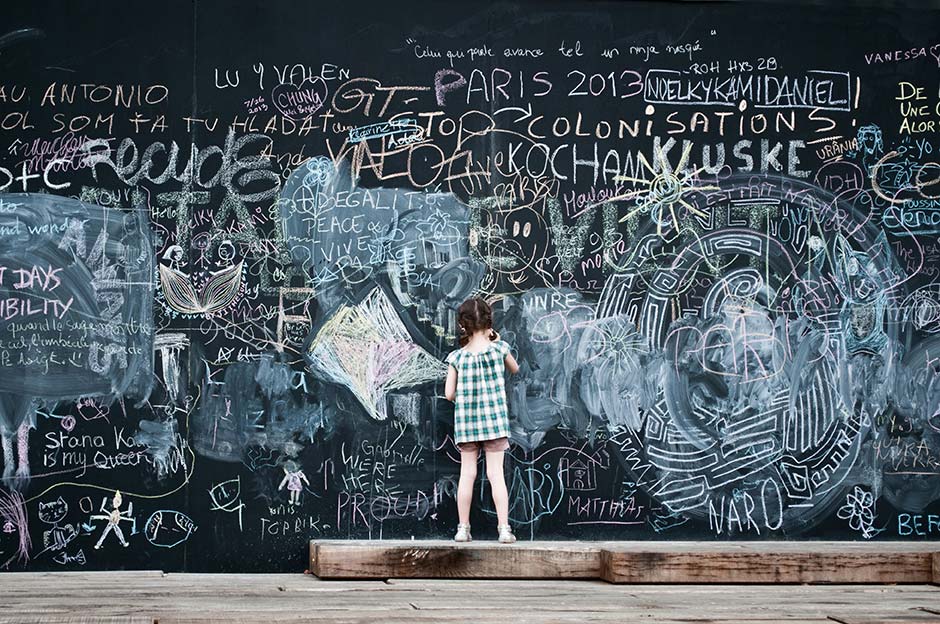

No, I do not want you to think about destruction, but simply think about what it is that you see, and what you do not see. We feel safe in what we can observe and see in Karl, because we can analyze that and we think we can find ways to intervene. But then we try our interventions and for some reason what we thought we saw does not quite work out the way that we logically thought it would. The difference is in what is lying underneath the surface.

Embed from Getty Images

The iceberg below the surface is all of the developmental pieces that have to come together in order to execute and learn efficiently. What we see now is a direct result of Karl’s understanding of his own body and his own way of interpreting the world. What we do not see is where it is coming from. If we simply attempt to navigate around the tip, we are frequently disappointed in our efforts and we jump from one intervention to another, thinking the intervention is at fault. It frequently is not the intervention, but the timing of the intervention.

What is a developmental delay? On paper we state that Karl may be 1 or 2 years behind in reading, math or social maturity to name a few, but what are we actually saying? Why is it a “developmental” delay? Because quite simply Karl’s nervous system has not matured to the level commensurate to his peers. Why do we keep insisting he must look, behave and learn like his peers on the very same activities that his peers are doing? How are we matching Karl? At what level of development does he feel most comfortable to learn from at this moment in time?

What we see now is a direct result of Karl’s understanding of his own body and his own way of interpreting the world. What we do not see is where it is coming from.

So many families believe in tally sheets of checking off that their “Karl’s” have gotten 8 out of 10 today or 5 out of 6 trials today and I frequently wonder at the functionality of it all. If Karl is working away at an activity or an expectation beyond the maturity of his central nervous system, what does these tally sheets matter? Are we training his cognitive brain to do what his central nervous system disallows him to do? Is the only answer we have for him to cope and accommodate his system rather than to remediate and alleviate the pressure of the developmental delay? What does it matter if Karl can memorize aspects rotely and can learn to do something in a certain way, but it holds no meaning for him to generalize this same skill in a different time, space or environment.

The brain is far more complex than simply looking at Karl’s learning behavior. He is more than that and he deserves to be known at the level commensurate to his maturity level. The beauty of matching his developmental level is that you can apply targeted intervention aimed at the more precise point of origin and have far longer lasting success that comes from within and enables Karl to chip away at the iceberg underneath the surface himself and navigate his own ship through the murky waters of uncertainty, slower processing speed and gray areas of social-emotional maturity that is so hard to teach.

In the next couple of blogs I am going to focus on different aspects of executive functioning and what is necessary to develop these areas of function.

May your journey be fruitful in 2017!

Maude

by Maude Leroux | Dec 20, 2016 | Parenting

I am sure that most families right now are getting ready for the bustle of end of year activity with great amounts of energy. It is family time for most and also catching up with friends you have not heard from in a long while. We are all engaging in reflecting on the past year and recalling wondrous moments, as well as times where it would have been better to simply not have left the bed!

Children reflect in their play. This is likely the most misunderstood aspect of childhood as the world interferes with activity that requires product and not process. We all want to see what the child can do, what the child can accomplish and we want to answer the question of how far did we comes this year. It would be so great to measure our success by what we can see or observe in every day life.

Yet, the child does so many things unseen by us. We know that they listen, that they perhaps can use language effectively, that they can build a structure, but do we know their thoughts? Is there truth to “you are what you think you are”? Why do we sometimes observe behavior that is not logical to the moment, that interferes with our wishes for a child’s behavior, and that is not deemed “publicly appropriate”? Do we truly understand why the child engages in what he or she does?

When children play they experience the world as they see it. They control the play. They choose the activity, the characters, the symbols and the scenes. They play out what is important to them.

Children are developing minds, not developing bodies alone. They have to figure out their world with what they have available to them in their own capacities of understanding. Each experience you have had in the past is linked to a limbic memory (emotional memory) and we bury these experiences with their emotions in the subconscious regions of our mind. When we recall these past events, we immediately feel the emotion that went alongside with it. We do not learn to do this as adults, but when were developing as children. The memories you are making during this end of year family time are going to become one of those subconscious limbic memories.

When children play they experience the world as they see it. They control the play. They choose the activity, the characters, the symbols and the scenes. They play out what is important to them. The two year old may play out a lot of “baby” themes as they embark on this exciting but scary world of exploration, especially if mommy has a new baby to pay attention to. The 4-year may play out big monster and scary themes as they stand on the important precipice of discovering their own self-identity and also gain a few nightmares in this process. The 5 year old may play out his ambivalence toward going to the “big school” next year and the need to still be cuddled and nurtured and not to be expected to “grow up”. The Kindergartner may play out teacher and children themes to figure out authority and the limits of his own autonomy. Other times children play out experiences in their lives like going to the doctor or dentist or some happy family event like going to the beach.

Embed from Getty Images

It is during play that the child is learning the very self-reflection that we as adults take for granted every day. Can you imagine not having the ability to think back on loved ones you may have lost? Or not to have the ability to think on how you solved a similar problem before, so you could engage in a similar strategy again? How do you measure this ability? How do you rate this ability in importance? Yet, we can get so stuck on only what we are able to see. What is my child eating, how is she writing, or speaking, but rarely “how is she thinking” and how does her self-reflection affect her daily performance. How is she developing her self-esteem and sense of self based on her experiences? We are so engaged in goals in every realm of activities of daily living, but do we really know the mind of our child?

We frequently see a strong phenomenon at our center in a number of kids we serve. They may go through the physical part of our program quite well and achieve great results, but they may still exhibit behaviors at home or school that looks like nothing has changed. This is so frustrating for families who are so invested in seeing their little one do better. In actual fact, they are doing better, but their own minds have not made that emotional leap as yet to simply trust the new experiences and let go of the past uncomfortable learning experiences. This frequently takes time and requires a certain amount of play to process the emotional mind’s adaptive response to their “newer” nervous system. In play the children will choose themes that are dear to them; the child who is bedwetting still may put a toilet in the middle of a wild forest; the child with an eating disorder may choose a whale to feed; the child who lacks a sense of power may become the biggest wizard of all times! The list goes on. Children will frequently play the character they most fear or not understand so they could practice seeing the perspective of both sides. Frequently they will bring up themes from past “traumatic” experiences that they will re-enact with the “new” experiences to make sense of the past.

I can go on and on, but really want to leave you with one thought during this end-of-the-year time. How barren would your life have been if you did not have the ability to self reflect and make sense of past experiences? How much attention are you paying to the developing growth of the mind of your child to achieve this same amount of fullness?

Warm hugs to everyone!

Maude

by Maude Leroux | Nov 23, 2016 | Social Skills

For this blog I requested the Speech Language Pathologist at our office to support us. She can be reached via my e-mail at maude@atotalapproach.com

As a parent of two middle schoolers I am frequently finding myself in the midst of conversations about “the populars” and “the wierdos” and where in this social strata my girls see themselves. The one group has the right clothes and hair and seems to attract everyone with their aura. The other seems to be out of sync with the world, they just don’t seem to “get it” and remain loners. As a speech-language pathologist I find myself dissecting the interactional patterns of these teens as I attempt to understand what makes some social gymnasts and others appear as clumsy misfits. In this world of social media, where behaviors are examined, scrutinized, criticized, judged and on occasion lauded, it is certainly not surprising that so many of our young ones end up with us therapists who try to undo the damage that their peers have inflicted upon their developing minds. Parents want nothing more than to see their child succeed in every aspect of their school career and feel that they know how to swoop in and save then from academic failure but when it comes to social interactions they feel that they are at a loss. How does one help their 12 year old son join an impromptu soccer game? Or their 12-year-old daughter to join a group of kids at the lunch table? These seemingly simple issues that unfortunately make or break the middle school years.

Embed from Getty Images

So what makes some kids so socially adept? The one everyone wants to be around, the ones the teachers love and parents encourage their kids to befriend. The answer is praxis. Praxis is the ability to formulate, plan and execute a motor plan and serves as the basis for executive function skills; the ability to move through life in a smooth and fluid manner that results in social success. This succinct three – part plan appears simple yet it is intricate and complicated, heavily based in internal timing and sensory integration. Well developed praxis skills is the ultimately represented in strong social skills that allows one to think and react online and while responding to changing emotions and often accosted by a myriad of sensory stimuli.

The initial step to motor planning begins with an idea. In the case of social interaction it can be seen as an idea of how to initiate a conversation, how to respond with a comment, questions, quip, non-verbal response. The teens who are socially adept are able to figure out how to join in on a conversation, what sort of vocabulary they can use with peers vs. friends vs. adults, what topics are appropriate for a given context, when to move on to the next idea, read the mood of the conversation and judge whether or not to crack a joke. The fascinating idea is that these decisions are made sub-consciously and with split second timing. For the kids who are socially awkward conversation is stilted and often leads to odd looks and stares from peers. Simply knowing what to say is only the first step to the process.

In wanting the best for our children we often over estimate what our young ones are capable of and the demands we place on them are often way more than they are ready to handle. Not all children are born to be the class representative, or have a group of best friends at the start of middle school. Some may need more hand-holding, guidance and practice in navigating the social world.

Once the seed of the idea is conceived the next step is to plan. These young minds need to retrieve the right vocabulary to talk to the cute boy they just met, or answer their science teacher’s questions. These responses need to be timely, accurate and exact in order to be taken seriously. Groping for the right words, using ambiguous phrases leads to confusion and ultimately lack of interest and breakdown in the flow of conversation. When an interaction goes south our kids are left feeling rejected or defeated and the next time a situation arises are less likely to want to put themselves out there. The negative emotional feedback they receive from this unsatisfactory attempt at interaction compounds on itself leading to a sense of failure.

The final culmination of this complex series of events is execution of the idea and the carefully laid out plan. It is almost as if you have the lyrics to a song but now you have to set them to music. Our young ones have take their idea and a plan and now need to deliver it using thoughtfully chosen vocabulary and grammar, with appropriate tone all while adding accurate eye-contact and gestures. A slight discrepancy in timing could look like lack of interest? Mocking? The ones that get it right on the first time are rewarded with positive emotional feedback and motivated to keep flaunting their social skills. The ones that frequently stumble feel their social inadequacies and are less likely to want to try again.

In order to help our kids navigate these complicated social worlds, it is important for the adults in their lives to really understand what is expected of them and how hard they are having to work everyday trying to be part of the social scene. While some can go through their day not having to think much about how to make friends or how to converse with their teachers, others have to use much of their cognitive resources in order to decide what to say, how to lay out the linguistic form of their thoughts and then finally how to actually verbalize their ideas in a manner that sounds authentic. The whole process can be taxing and often overwhelming and frequently leads to teens choosing to opt out of spending time with peers. In order to fill their schedules they look for other more emotionally fulfilling options like the computer and social media. Social media is often an easier medium for some kids to adapt to; there is more time available to formulate responses, no burden of monitoring body language, gestures or eye-contact. It is no wonder that some teens prefer to sit in front of a screen rather than face to face with other kids who talk and move too fast for them to process. In wanting the best for our children we often over estimate what our young ones are capable of and the demands we place on them are often way more than they are ready to handle. Not all children are born to be the class representative, or have a group of best friends at the start of middle school. Some may need more hand-holding, guidance and practice in navigating the social world.

Mahnaz N Maqbool, MS CCC-SLP

by Maude Leroux | Oct 18, 2016 | Praxis

How do we know what children hear? How are they listening to our language? How do we know they are not responding due to not being able to sequence and use language in the right order, or not being able to plan a motor sequence? These are interesting questions, are they not? To answer them requires a certain amount of self-reflection, especially to ponder the multi-facets of children in all their wonderful ways, including the challenges.

Let’s first understand praxis and be sure we all carry the same understanding. Praxis entails multiple different components, built on several building blocks of foundation, which has to be accomplished in order to acquire the skill of praxis. As a definition, praxis contains the ability of the nervous system to ensure a timed, coordinated response from the motor system of the body, while also contemplating how the limbic system (emotions) feels about it. Without this function, we potentially feel helpless, as if we have no power, no way to enact upon this world and many times, the only recourse we have is the Amygdala in fight, flight, or freeze, because it does not require sequencing, simply a reflexive response. In fact, praxis is what gives us planful, executive behavior.

The real story is that it is all interconnected. With what we know as therapists today, we simply cannot intervene in a child’s life in isolation any longer.

Praxis is built on the foundation of having the ability to regulate (modulate) our different senses. If our nervous system is disorganized, it is very difficult to build planful behavior, as praxis requires a calm state in the nervous system. It also relies very heavily on our ability to discriminate with our different senses, so we know how hard to push a cart, how to feel what we hold in our hand, how we see the object in the distance we see it, and how we hear the instruction given to us. The ability to register information and process it to the brain to be analyzed, is the cornerstone upon which we can build constructive play that would contain purpose and meaning, and result in planful behavior. Without these building blocks, we will struggle to achieve the multiple forms in which praxis occurs. We need praxis to play!

The totality of praxis relies on first having a motor idea, initiating this idea, sequencing through the idea, and to culminate in completing this idea within the same timing and rhythm as our peer. As we complete the activity, our body also registers feedback that supports us to repeat that action. Feedback is important for self-motivated (intrinsic) repetition, such as you see the new toddler do when they pull themselves together after taking the first step to attempt the second step. An amazing process to watch unfolding in front of our eyes and no parent is more proud of witnessing this moment.

Which brings us to the thinking around language and praxis and their co-influence on each other. It is essential that we first consider non-verbal communication as therein lies much of the difficulty with our kids that also exhibit praxis difficulties. It is the primary job of the infant to cultivate increasingly complex non-verbal gesturing to support the meaning and context of what is to develop in verbal skill later. If the child is experiencing poverty in their ability to plan their movements, we have to consider the impact this would have on their ability to use gestures. It is a well-known fact that communicating a clear message depends 80% on your non-verbal communication to each other. It is what supports the meaning of context and without it, you become no more than a “talking head”. These children develop into kids who rely so much on facts and what they can grasp in black and white, that the underlying meaning, the different social nuances become lost on them. It becomes a sad world in which it becomes increasingly difficult to connect with others and no amount of social skills classes can replace the exquisite automaticity that this requires from our system.

Embed from Getty Images

Speech Language Pathologists frequently discuss the language model proposed by Bloom and Lahey, which explains three components of language: Form, content and use. The Form of language is the tangible part. It consists of the phonology (sound), morphology (different morphemes in words), and syntax. It starts with single words, develops into two word phrases, adding plurals, and then culminates in the formation of sentence structure. This process is very reliant on sequencing, though there are two forms of sequencing available to the speaker. The sequencing that involves the body and timed execution of gestures simultaneously with speech is one aspect. The other form of sequencing is understanding logical order through the cerebral cortex with intelligence and utilizing memory to support development in language. So it is possible to use language and become a fluent speaker while still experiencing praxis difficulties in the body. This type of speech development though often is very bound to intelligence and though the speaker can maintain fluid speech on a topic, the speech might lack the prosody and tonality of voice modulation, and the rhythm of a back and forth communicative effort. Such persons may also have difficulties in social skills as the speaker has not developed the integration of gestural and verbal communication causing a lack of understanding in hidden and abstract meaning.

This brings us to content part of their model, which includes meaning expressed through words. In terms of language development, it also contains the development of action words, location words, and descriptive words. Children struggling with praxis have difficulty figuring out the “how to” of things and pairing physical problem solving with action words is a frequent technique to use in sessions.

The use of language is the third component of the model. The child has to understand why she is communicating, which involves an abstract formation of having meaning to communicate. Frequently parents are so proud of the words and sentences their child can repeat back or use when prompted. This expression frequently does not come from the place of meaning. Using language is one aspect, communicating with language is the fuller aspect. The sense of purpose and goal directedness behind her language is reliant on the building block of abstract formation and ideation, which is formalized through the use of sequential order.

The real story is that it is all interconnected. With what we know as therapists today, we simply cannot intervene in a child’s life in isolation any longer. Families need evaluations from both occupational and speech language therapists that understand this overlap, can assess it and can formulate a plan to build this in an integrative way for each individual profile. We need to bring a team around each child that will consider the different goals of the child in a way that would respect the child’s entire profile in order for her to become intrinsically motivated to turn towards learning and simply… fly!!!

Maude Le Roux, OTR/L, SIPT

Recent Comments